Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act: How It Built the Legal Foundation for Generic Drugs

Nov, 10 2025

Nov, 10 2025

The Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FD&C Act) isn’t just an old law from 1938-it’s the backbone of every generic drug you pick up at the pharmacy today. Before this law, companies could sell anything as medicine with no proof it was safe. In 1937, over 100 people died after drinking a liquid antibiotic laced with poison. That tragedy forced Congress to act. The FD&C Act gave the FDA real power: no drug could hit the market without proof it was safe. But safety alone wasn’t enough to make generics possible. That came decades later, through a quiet but revolutionary update called the Hatch-Waxman Amendments.

Before Generics: A Broken System

In the 1970s, if you wanted to make a generic version of a brand-name drug, you had to start from scratch. You needed to run full clinical trials-just like the original maker-to prove your version worked. That meant spending $50 million to $100 million and waiting 10 years. Most companies didn’t bother. Only about 19% of prescriptions filled in the U.S. were for generics back then. The rest? Brand-name drugs, often at full price. The system wasn’t broken by accident-it was designed that way. Patents gave brand companies exclusive rights. But the law didn’t give generics a fair way in.

The Hatch-Waxman Breakthrough

In 1984, Congress changed everything. The Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act-better known as the Hatch-Waxman Amendments-rewrote the rules. It added Section 505(j) to the FD&C Act, creating the Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) pathway. Suddenly, generic makers didn’t need to repeat clinical trials. They only had to prove one thing: their drug was bioequivalent to the brand version. That meant the same active ingredient, same strength, same form (pill, injection, etc.), and the same rate and amount of absorption into the bloodstream. The FDA requires bioequivalence to be within 80-125% of the brand drug’s levels. That’s not a guess-it’s science, backed by blood tests and pharmacokinetic studies.

This wasn’t just a shortcut. It was a game-changer. Generic companies could now focus on manufacturing, not reinventing the wheel. The FDA’s Office of Generic Drugs, led by experts like Dr. Darby Kozak, began reviewing applications faster and with more consistency. Today, nearly 95% of ANDAs get approved within 10 months. Back in the 1990s? It took over 30 months.

How Generics Got Their Incentive

Hatch-Waxman didn’t just make it easier-it made it worth it. The law gave the first generic company to challenge a brand drug’s patent a 180-day window of exclusive market access. That’s huge. During those six months, no other generic can enter. That’s enough to recoup development costs and make a profit. It’s why companies like Teva, Sandoz, and Mylan spend millions on patent lawsuits. They’re not just fighting for market share-they’re fighting for that 180-day prize.

At the same time, brand-name companies got something back: patent term restoration. If a drug took five years to get FDA approval, the patent clock could be extended by up to five years. But the total patent life couldn’t go beyond 14 years from approval. That balance kept innovation alive while opening the door for competition.

The Orange Book: The Secret Map to Generics

If you’re trying to make a generic drug, you don’t just look up the brand name. You go to the FDA’s Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations-better known as the Orange Book. It’s a public database listing every approved drug and its therapeutic equivalence rating. It also shows every patent linked to the brand drug and whether a generic applicant has certified against it. That’s how the whole patent challenge system works. If a generic company says, “We’re not infringing,” and wins in court, they get that 180-day exclusivity. The Orange Book isn’t just a list-it’s the rulebook for generic competition.

Where the System Still Fails

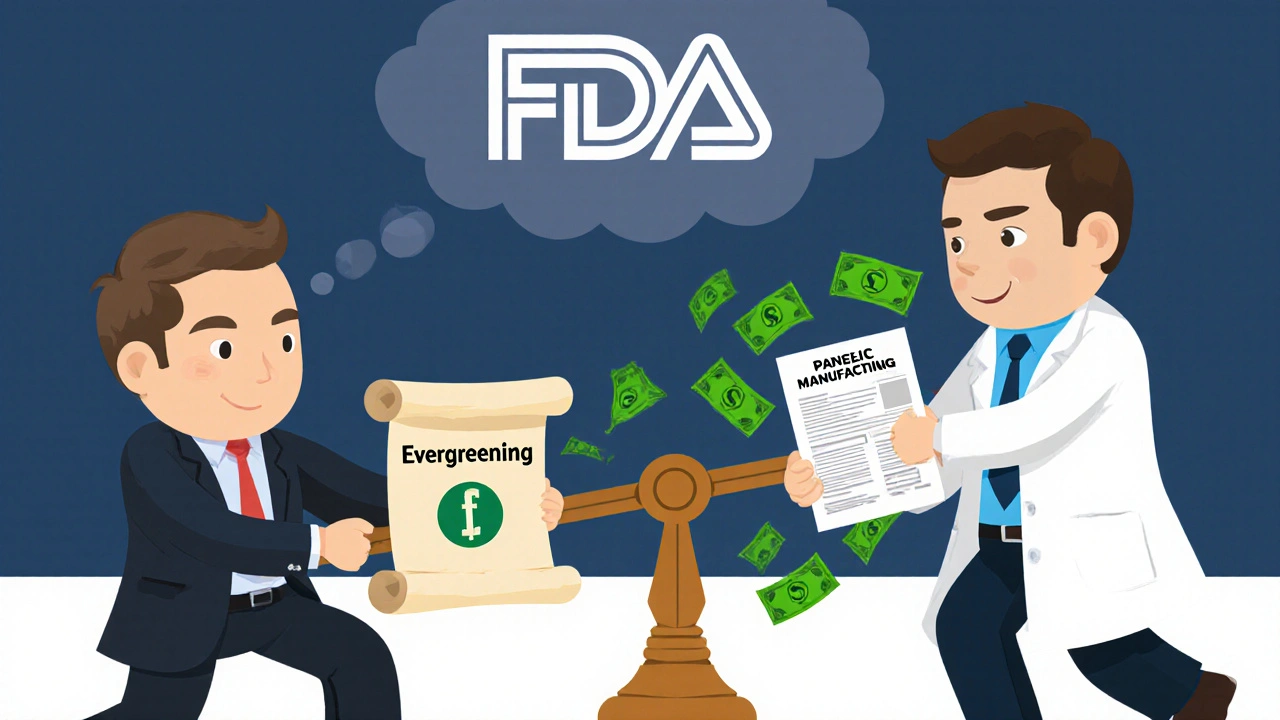

Despite its success, the system has been gamed. Brand companies now use “evergreening”-filing new patents on minor changes like coating, dosage form, or delivery method-to delay generics. They file citizen petitions to the FDA, asking for more data, knowing the review will stall. Sometimes, they pay generic companies not to enter the market. These tactics, called “pay-for-delay,” have been challenged by the FTC, but they still happen.

Complex drugs are another problem. Inhalers, injectables, and biologics are harder to copy than a simple pill. The FDA has only recently started creating clear guidance for these. As of 2023, generic entry for complex products is 42% lower than for small-molecule drugs. That means patients still pay high prices for things like asthma inhalers or insulin pens.

Compliance and Enforcement

Making a generic drug isn’t just about science-it’s about law. Every manufacturer must follow current Good Manufacturing Practices (cGMP). The FDA inspects facilities regularly. In 2022 alone, 47 warning letters were issued to generic drug makers for violations. The most common? Poor quality control and data manipulation. One company was caught deleting test results. Another used fake samples to pass inspections. Violations can lead to fines up to $1.1 million per incident-or criminal charges. The FD&C Act doesn’t just approve drugs-it enforces them.

The Impact: Billions Saved, Lives Changed

The numbers speak for themselves. In 1984, generics made up just 3% of total drug spending. Today? They account for 90% of prescriptions but only 17% of spending. That’s a $2.2 trillion savings for U.S. consumers over the last decade, according to the FTC. The Congressional Budget Office estimates the current system will save another $158 billion by 2032. Without the FD&C Act’s evolution, most Americans couldn’t afford their medications. Diabetics wouldn’t be able to buy insulin. Cancer patients wouldn’t get their chemo pills. Heart patients wouldn’t refill their statins. Generics aren’t just cheaper-they’re essential.

What’s Next?

The FDA’s 2023-2027 plan calls for modernizing the generic pathway for complex products. New guidance is coming for nasal sprays, eye drops, and injectables. The CREATES Act of 2019 is helping by forcing brand companies to share samples so generics can test their products. The GDUFA program, now in its third iteration, ensures the FDA has the funding and staff to review applications faster. But the real test will be whether the system can keep up with new drug types-like biosimilars and personalized medicines. The FD&C Act was built for pills and syrups. Now it’s being stretched to cover gene therapies and AI-driven drug design. The law is old, but its framework is still holding.

What is the FD&C Act and why does it matter for generic drugs?

The Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FD&C Act) is the 1938 U.S. law that gave the FDA authority to regulate drug safety. It didn’t originally allow generics, but it created the legal structure that made them possible. The 1984 Hatch-Waxman Amendments added Section 505(j), which established the ANDA pathway-letting generic companies prove equivalence without repeating clinical trials. Without this law, generics as we know them wouldn’t exist.

How do generic drugs get approved today?

Generic drugs are approved through the Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) pathway under Section 505(j) of the FD&C Act. Manufacturers must prove their product has the same active ingredient, strength, dosage form, and route of administration as the brand-name drug. They must also show bioequivalence-meaning the drug is absorbed into the bloodstream at the same rate and extent, with 90% confidence intervals for Cmax and AUC falling between 80% and 125% of the reference drug. No new clinical trials are required.

What is the Orange Book and how is it used?

The Orange Book, officially titled Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations, is the FDA’s public database that lists all approved drug products and their therapeutic equivalence ratings. It also shows patents associated with brand-name drugs and the type of patent certification submitted by generic applicants. Generic manufacturers use it to identify which patents they must challenge to enter the market and to qualify for 180-day exclusivity.

Why do some generic drugs still take years to reach the market?

Even with the ANDA pathway, delays happen. Brand companies often file secondary patents on minor changes-like a new pill coating or delivery method-to extend exclusivity. They may also file citizen petitions with the FDA to request more data, slowing approval. Some even pay generic companies to delay entry (pay-for-delay). Complex drugs like inhalers or injectables are harder to copy and lack clear FDA guidance, which slows approval. Patent litigation can also drag on for years.

Are generic drugs as safe and effective as brand-name drugs?

Yes. The FDA requires generics to meet the same strict standards for quality, strength, purity, and stability as brand-name drugs. Bioequivalence studies prove they work the same way in the body. The FDA inspects generic manufacturing facilities just as often as brand-name ones. In fact, many brand-name companies make their own generics under different labels. There is no clinical difference in safety or effectiveness between approved generics and their brand counterparts.

What happens if a generic drug manufacturer violates the FD&C Act?

Violations can lead to serious consequences. The FDA issues warning letters for issues like poor quality control, data falsification, or failure to follow cGMP. In 2022, 47 warning letters were sent to generic manufacturers. Companies can face civil penalties up to $1,100,194 per violation. For intentional fraud or falsified data, criminal prosecution is possible-including prison time. The FDA can also seize products or ban imports from non-compliant facilities.

Ryan Everhart

November 11, 2025 AT 05:38So the FD&C Act was basically the FDA’s first real power move after that poison drug tragedy? Wild how one law changed everything. I mean, imagine if they just let companies sell whatever they wanted as medicine today. We’d all be taking candy pills with ‘maybe works’ on the label. 🤷♂️

David Barry

November 12, 2025 AT 20:24Let’s not romanticize Hatch-Waxman. The 180-day exclusivity window created a cartel dynamic where the first filer gets rich while others wait. And don’t get me started on pay-for-delay - it’s legal bribery disguised as litigation. The FTC’s been screaming into the void for 20 years. Meanwhile, insulin prices? Still absurd. This isn’t a system. It’s a game with rigged rules.

Alyssa Lopez

November 13, 2025 AT 22:34Generic drugs rly saved my life but the FDA inspections? Total joke. I work in pharma and saw a plant get flagged for data falsification then approved 3 months later. They’re understaffed and overpoliticized. cGMP? More like cGMP if you’re lucky. The Orange Book? A maze. I’ve spent weeks just figuring out which patent to challenge. And don’t even mention biologics - they’re just brand drugs with a new coat of paint.

Alex Ramos

November 15, 2025 AT 07:58Just wanted to say thank you for this breakdown - seriously. I’m a med student and this is the clearest explanation I’ve seen of ANDA vs NDA. Bioequivalence being 80-125%? Mind blown. And the Orange Book is like the secret decoder ring for generics. 🙌 Also, real talk - my grandma’s on 5 generics and she pays $4 a month. Without this? She’d be choosing between food and insulin. Thanks for the deep dive. ❤️

edgar popa

November 15, 2025 AT 18:19Generics are the unsung heroes of healthcare. No cap. I used to think they were ‘weaker’ until I saw my bloodwork. Same results. Same side effects. Same everything. Why pay $300 when you can get the same pill for $5? The system works. Let’s not break it.

Eve Miller

November 16, 2025 AT 17:25It is deeply concerning that the term ‘bioequivalence’ is so frequently misunderstood by the public. The FDA’s requirement that AUC and Cmax fall within 80–125% of the reference product is not arbitrary - it is statistically validated, peer-reviewed, and rigorously enforced. To suggest otherwise is not merely inaccurate; it is dangerously misleading. The science is sound. The skepticism is not.

Chrisna Bronkhorst

November 18, 2025 AT 14:45Pay-for-delay is the real cancer here. Big Pharma pays generics not to compete? That’s not capitalism - that’s feudalism with lawyers. And the Orange Book? A battlefield. I’ve seen companies file 15 patents on a pill just to block generics. The FDA’s got no teeth. And the worst part? Most people don’t even know this is happening. They just think their meds are expensive because ‘healthcare is broken’. Nah. It’s because someone’s pocketing the difference.

Amie Wilde

November 20, 2025 AT 12:32My dad’s on a generic statin. Pays $3. He used to pay $400. No joke. I’m just glad someone finally made it possible. Don’t fix what ain’t broke.

Gary Hattis

November 22, 2025 AT 01:42Coming from South Africa, I’ve seen how this system saves lives globally. Most of the HIV meds we use? Generics from India and the U.S., made possible by Hatch-Waxman’s framework. The law’s not perfect - but it’s the only reason millions outside the U.S. can access treatment. When you’re choosing between medicine and your kid’s school fees, 90% of prescriptions being generic isn’t policy - it’s survival. The FD&C Act didn’t just change American healthcare. It changed global health equity.