How Bladder Stones Trigger Urinary Tract Muscle Spasms

Oct, 7 2025

Oct, 7 2025

Bladder Stone Symptom Checker

This tool helps identify symptoms that may indicate bladder stones and associated muscle spasms. Remember, this is for educational purposes only and not a substitute for medical diagnosis.

Common Symptoms

- Urgency to urinate 1

- Painful urination 2

- Lower abdominal cramps 3

- Blood in urine 4

- Recurring UTIs 5

Risk Factors

- Enlarged prostate

- Neurogenic bladder

- Chronic catheter use

- High protein/salt diet

- Dehydration

Ever felt a sudden, sharp cramp in your lower belly right after a bathroom visit? That pain could be more than a harmless twitch - it might be linked to bladder stones. Understanding how these tiny mineral deposits set off muscle spasms helps you catch the problem early and choose the right treatment.

Key Takeaways

- Bladder stones are hard mineral deposits that form inside the urinary bladder.

- Muscle spasms of the urinary tract occur when the bladder’s smooth muscle (detrusor) contracts involuntarily.

- Stone size, location, and composition can irritate the bladder lining, triggering reflex spasms.

- Symptoms often overlap: urgency, painful urination, and lower‑abdominal cramps.

- Diagnosis combines imaging, urine analysis, and symptom review; treatment ranges from lifestyle changes to minimally invasive procedures.

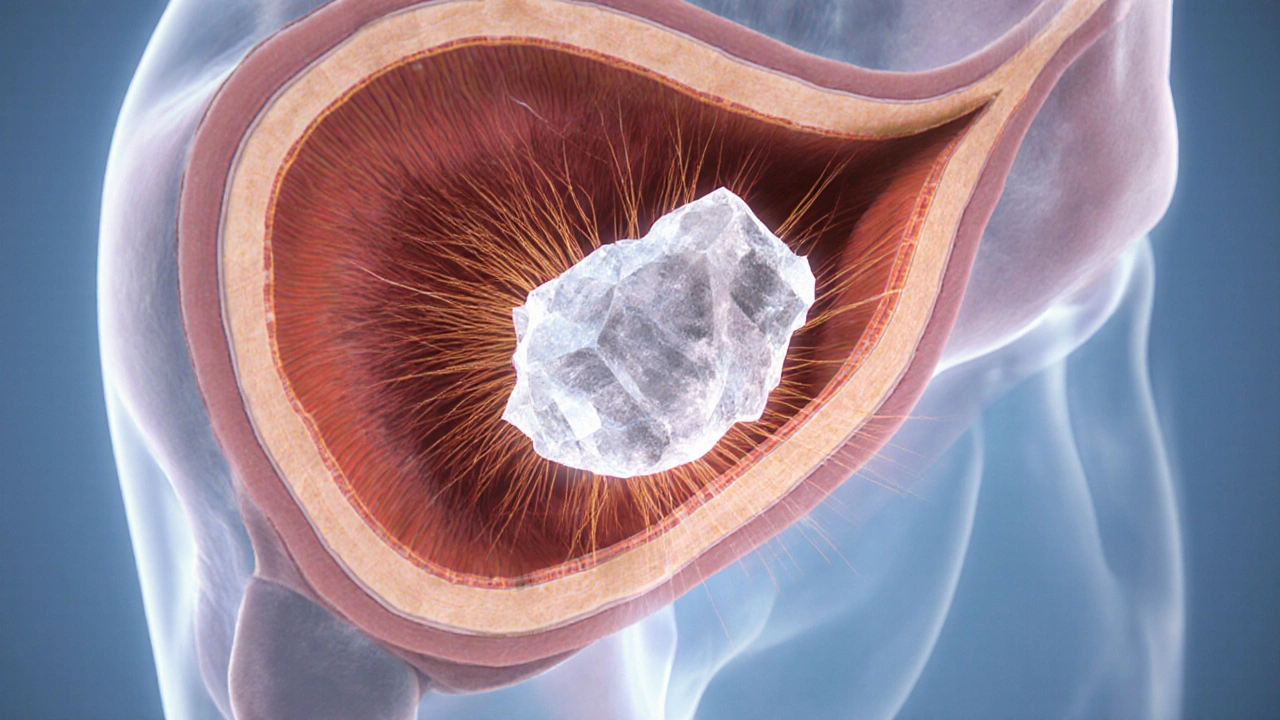

What Are Bladder Stones?

Bladder stones are hard, crystalline formations that develop within the urinary bladder. They typically consist of calcium salts such as calcium oxalate or phosphate, but can also contain uric acid or struvite, especially in people with recurrent urinary tract infections (UTIs).

Most bladder stones form when the bladder cannot empty completely. Stagnant urine provides a perfect environment for minerals to crystallize. Factors that increase risk include enlarged prostate, neurogenic bladder, chronic catheter use, and diets high in protein or salt.

What Are Urinary Tract Muscle Spasms?

Muscle spasms of the urinary tract refer to sudden, involuntary contractions of the bladder’s smooth muscle, called the detrusor. These spasms cause a rapid urge to urinate, sometimes accompanied by pain or a “tightening” sensation.

Spasms can be neurogenic (originating from nerve signaling problems) or myogenic (originating from the muscle itself). Common triggers include bladder irritation, infection, stones, or over‑distension.

How Bladder Stones Lead to Muscle Spasms

The connection hinges on irritation and reflex pathways. As a stone rubs against the bladder lining, it causes micro‑injuries and inflammation. The bladder wall contains sensory nerves that send signals to the spinal cord. When these nerves detect irritation, they can trigger a reflex arc that tells the detrusor muscle to contract suddenly-resulting in a spasm.

Three physiological mechanisms are most frequently cited:

- Mechanical irritation: Larger stones (usually >5mm) physically press on the urothelium, prompting local inflammation.

- Chemical irritation: Certain stone compositions, especially struvite formed during UTIs, release alkaline substances that further inflame the bladder wall.

- Neuro‑genic reflex: The bladder’s afferent nerves fire excessive signals, leading to detrusor over‑activity.

These mechanisms often act together, meaning even a small stone can cause spasms if it’s chemically aggressive or positioned near the bladder neck.

Symptoms Overlap - What to Watch For

Both conditions share several red‑flag signs. If you notice any combination of the following, seek medical advice:

- Sudden, intense urge to urinate that doesn’t subside after a few seconds.

- Painful, burning sensation during or after urination.

- Lower‑abdominal or pelvic cramps that feel like “muscle twitches.”

- Blood in the urine (hematuria), especially after a spasm.

- Recurring urinary tract infections.

While occasional urgency can be normal, persistent episodes often signal underlying irritation-most commonly from a stone.

Diagnosing the Connection

Doctors start with a detailed history and physical exam, then move to targeted tests.

- Urine analysis: Checks for infection, crystals, or blood.

- Ultrasound: First‑line imaging that can spot stones as small as 2‑3mm.

- CT scan (non‑contrast): Gold standard for stone detection; it measures size, number, and composition.

- Urodynamic studies: Evaluate bladder pressure and muscle activity, confirming spasms.

When a stone is identified alongside abnormal urodynamic results, the link becomes clear.

Treatment Options - From Lifestyle to Surgery

Management aims to remove the stone, reduce irritation, and calm the bladder’s muscle activity. Below is a quick comparison of the most common approaches.

| Method | How It Works | Typical Success Rate | Key Drawbacks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Increased hydration & dietary changes | Dilutes urine, prevents crystal formation | 70‑80% for small (<4mm) stones | May not affect larger stones |

| Medication (α‑blockers, anticholinergics) | Relaxes bladder neck, reduces spasm frequency | 60‑70% symptom relief | Side effects: dry mouth, dizziness |

| Lithotripsy (shock‑wave) | Breaks stone into fragments that pass naturally | 85‑95% for stones <10mm | May cause temporary hematuria |

| Cystolitholapaxy | Endoscopic removal using a laser or basket | 95‑99% complete removal | Invasive, requires anesthesia |

| Surgical open removal | Direct extraction via abdominal incision | 100% for very large or multiple stones | Longest recovery, higher infection risk |

For most patients, the first line is lifestyle modification combined with medication to calm spasms. If the stone persists or symptoms remain severe, minimally invasive options like lithotripsy or cystolitholapaxy become the go‑to choices.

Preventing Future Stones and Spasms

Prevention hinges on two pillars: keeping urine dilute and protecting bladder health.

- Hydration: Aim for 2.5-3liters of fluid daily, preferably water. Spread intake throughout the day rather than gulping it all at once.

- Dietary balance: Limit excessive animal protein and salt, increase citrus fruits (citric acid can inhibit stone formation), and incorporate leafy greens rich in magnesium.

- Manage underlying conditions: Treat enlarged prostate, neurogenic bladder, or chronic UTIs promptly.

- Regular check‑ups: Annual ultrasound for those with a history of stones or persistent bladder symptoms.

- Medication adherence: If prescribed α‑blockers or anticholinergics, take them consistently to reduce spasm frequency.

These steps cut down the chance of another stone forming and lessen the irritation that drives spasms.

When to Seek Immediate Care

Some scenarios demand urgent attention:

- Sudden inability to urinate (retention).

- Severe, worsening pain not relieved by over‑the‑counter painkillers.

- Fever over 38°C with urinary symptoms - possible sepsis.

- Visible blood clots in the urine.

In the ER, doctors may place a catheter to relieve retention and start antibiotics if infection is suspected.

Living with the Condition

Many patients wonder if they’ll have to live with ongoing spasms. The answer is reassuring: once the stone is removed and any infection cleared, most people see a dramatic drop in spasm frequency. Ongoing bladder training-such as timed voiding and pelvic floor exercises-helps maintain normal muscle tone.

Support groups and online forums can also provide practical tips, from the best water bottles for hydration to recipes low in oxalates.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can a small bladder stone still cause severe spasms?

Yes. Even stones under 4mm can be chemically aggressive-especially struvite stones formed during infections. Their location near the bladder neck can trigger intense reflex spasms despite their size.

How long does it take to recover after cystolitholapaxy?

Most patients are discharged the same day. Full recovery-meaning normal bladder function without catheters-usually occurs within one to two weeks. Gentle activity and plenty of fluids speed up healing.

Is it safe to use over‑the‑counter painkillers during a spasm?

Acetaminophen or ibuprofen can help manage mild pain, but they don’t address the underlying cause. If spasms persist more than a few days, see a clinician for targeted medication.

Can dietary supplements prevent bladder stones?

Citrate supplements (like potassium citrate) can raise urinary pH, reducing calcium‑based stone formation. However, they should only be taken after a doctor confirms the stone’s composition.

What’s the difference between bladder stones and kidney stones?

Kidney stones form in the kidneys or ureters and often travel down to the bladder. Bladder stones originate or stay within the bladder, usually because urine isn’t fully expelled.

Christopher Stanford

October 7, 2025 AT 13:27These "symptoms" are just a marketing ploy, not real scianc.

Steve Ellis

October 24, 2025 AT 12:00Whoa, hold on!

Imagine finally understanding your body’s signals – it’s like the climax of a blockbuster movie where the hero finally discovers the hidden truth!

Don’t let the jargon scare you; you’ve got the power to take charge, hydrate like a champion, and seek help before things spiral.

Every cramp is a shout, not a whisper, so answer it with confidence and the right medical advice.

Jennifer Brenko

November 10, 2025 AT 09:32From a patriotic perspective, it is imperative that our healthcare system prioritize the swift identification of urinary tract anomalies, such as bladder calculi, to safeguard the vigor of our nation's populace. The physiological cascade linking stone-induced irritation to detrusor spasms is well-documented, and any delay in intervention betrays our collective responsibility to maintain public health excellence.

Harold Godínez

November 27, 2025 AT 08:05Totally agree, but just a heads‑up: “deturor” should be “detrusor,” and “calculi” is plural, so you might say “a bladder stone” when referring to a single one. Clear language helps everyone stay on the same page.

Sunil Kamle

December 14, 2025 AT 06:38Indeed, the literature is replete with studies that illustrate the reflex arc triggered by stone‑induced urothelial irritation – a marvel of human physiology, if one enjoys watching tiny crystals orchestrate a symphony of muscle contractions. While the academic tone may appear lofty, the practical takeaway remains simple: stay hydrated and consult a clinician before the drama escalates.

Michael Weber

December 31, 2025 AT 05:11The bladder, an often overlooked reservoir, embodies a delicate balance between storage and expulsion.

When mineral deposits aggregate within its confines, they introduce a foreign texture that the urothelium cannot ignore.

This tactile intrusion initiates a cascade of afferent signaling that traverses the sacral spinal segments.

The sensory neurons, upon detecting irritation, relay impulses to the pontine micturition center, demanding an immediate response.

The detrusor muscle, designed for coordinated contraction, receives this heightened input and may contract prematurely.

Such premature contractions manifest clinically as urgency, cramping, or painful voiding.

Moreover, the chemical composition of certain stones, particularly struvite, can alter local pH, further inflaming the bladder wall.

The resulting inflammation sensitizes nociceptors, lowering the threshold for muscle activation.

Repeated episodes create a feedback loop wherein each spasm predisposes the next, compounding patient discomfort.

Diagnostic imaging, especially non‑contrast CT, provides precise localization and size estimation of these calculi.

Urodynamic studies complement imaging by quantifying detrusor overactivity during bladder filling.

Therapeutic strategies range from conservative hydration to endoscopic lithotripsy, each aiming to eliminate the irritative source.

In cases where stone removal is successful, patients frequently report a marked reduction in spasm frequency.

Nonetheless, clinicians must remain vigilant for residual neurogenic bladder dysfunction that may persist despite stone clearance.

Ultimately, recognizing the mechanistic link between bladder stones and muscle spasms empowers both provider and patient to intervene before the condition escalates.

Blake Marshall

January 17, 2026 AT 03:43Yo, u r totally missin that even a tiny stone can still cause a spasm – it’s all about where it sits and the chemic stuff it releases.

Shana Shapiro '19

February 3, 2026 AT 02:16I understand how frightening those sudden cramps can feel; it’s like an unexpected thunderclap in the quiet night of your day. Knowing the link to bladder stones can bring some clarity, and it’s encouraging that many find relief once the stone is addressed.

Jillian Bell

February 20, 2026 AT 00:49What if the “research” they tout is actually a cover‑up, keeping us dependent on endless tests while the real solution-natural hydration and diet changes-gets buried? Keep questioning the narratives fed to us.