How to Prepare for Medication Needs during Pilgrimages and Treks

Dec, 15 2025

Dec, 15 2025

Thousands of people climb to high-altitude sacred sites every year-Mount Kailash, Everest Base Camp, Lhasa, Gosainkunda Lake-each journey a mix of faith, endurance, and risk. Many don’t realize how dangerous it can be to show up at 12,000 feet without preparing their medications properly. The air is thin. Water is scarce. Pharmacies are miles away. And if your insulin freezes, your inhaler runs out, or your headache turns into something worse, help could be 48 hours away. This isn’t just about feeling tired. It’s about survival.

Know Your Risk Zone

Altitude sickness doesn’t wait for you to be ready. It hits fast, and it doesn’t care if you’re 25 or 65. Once you hit 8,000 feet (2,438 meters), your body starts struggling to get enough oxygen. By 14,000 feet, nearly half of all trekkers will experience symptoms like headaches, nausea, dizziness, or shortness of breath. At 17,500 feet-where Everest Base Camp sits-43% of people develop moderate to severe symptoms, according to Mosaic Adventure’s field data.Most pilgrims fly or drive straight into high-altitude zones. That’s the problem. Your body needs time to adjust. Climbing too fast is like sprinting a marathon without training. The medical community calls this acute mountain sickness (AMS). Left untreated, it can become high altitude pulmonary edema (HAPE)-fluid in the lungs-or high altitude cerebral edema (HACE)-fluid in the brain. Both are life-threatening.

There’s no way around it: if you’re heading above 10,000 feet, you need a plan. Not just a pill. A full system.

Essential Medications to Pack

You’re not just packing bandages and painkillers. You’re carrying tools that could save your life-or someone else’s. Here’s what you absolutely need:- Acetazolamide (Diamox): The gold standard for preventing altitude sickness. Take 125 mg twice a day, starting one day before ascent and continuing for three days after reaching your highest point. It helps your body breathe faster and adjust to lower oxygen. Side effects? More frequent urination and tingling fingers-both normal. About 67% of users report these, but they’re not dangerous.

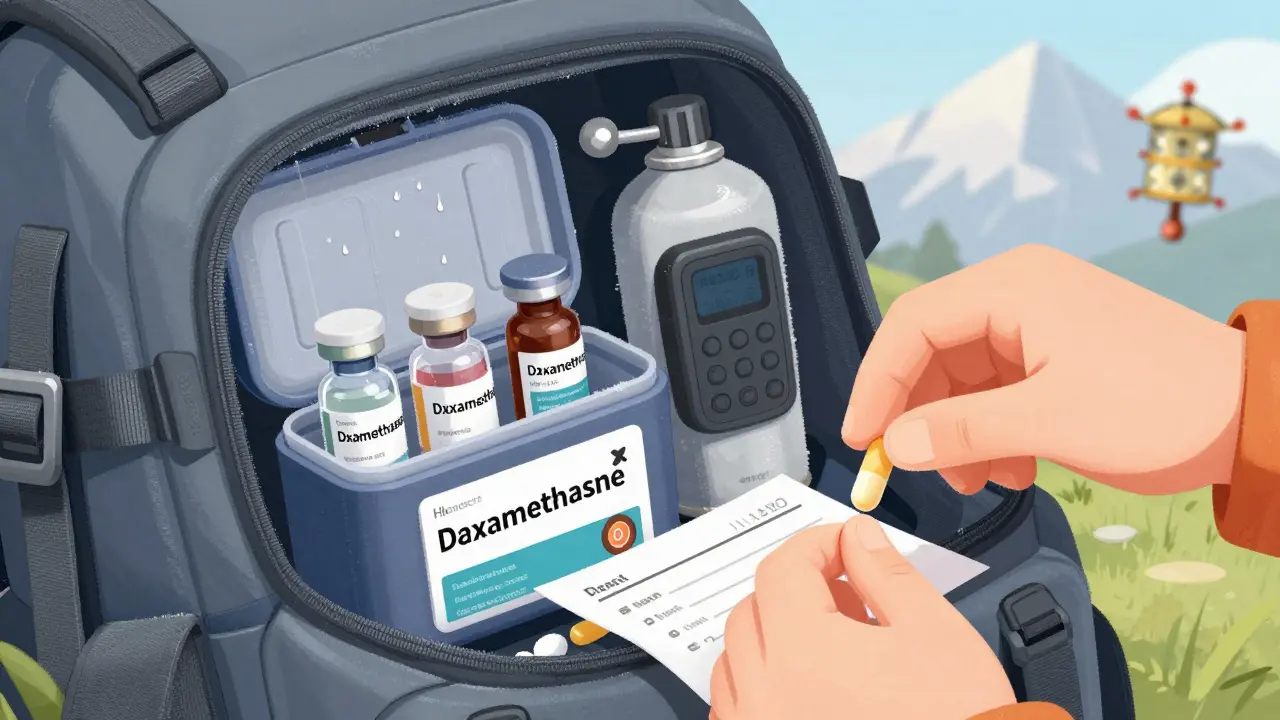

- Dexamethasone: A steroid used for treating HACE. If someone’s confused, stumbling, or vomiting uncontrollably, give 8 mg immediately, then 4 mg every 6 hours. This isn’t for prevention. It’s for emergency stabilization until descent is possible.

- Nifedipine (extended-release): Used for HAPE. Take 20 mg every 12 hours. It opens up constricted blood vessels in the lungs. Critical if someone’s coughing up frothy sputum or can’t catch their breath even while resting.

- Ibuprofen (400 mg): Reduces headache and inflammation. Often more effective than acetaminophen at high altitudes. Keep at least 10 tablets.

- Azithromycin (500 mg): For traveler’s diarrhea. Around 60% of trekkers get sick from dirty water. One 500 mg tablet daily for three days usually clears it up.

- Diphenhydramine (25-50 mg): For allergic reactions or severe itching. Useful if you get stung or react to unfamiliar plants or food.

- Antibiotic ointment and hydrocortisone cream: Small wounds heal slower at altitude. Infections spread faster. Don’t skip these.

And if you have a chronic condition? Bring extra. Double your usual supply. Insulin? Glucometers? Blood pressure pills? All of it. The Wilderness Medical Society says 22% of medical evacuations from high-altitude treks happen because someone ran out of medication-or it got ruined by cold or heat.

Storage Matters More Than You Think

Medications don’t survive extreme cold or heat well. Insulin loses 25% of its potency in just 24 hours if it drops below 32°F (0°C). Glucometers give wrong readings at 14°F (-10°C)-error rates jump to 18%. That’s not a glitch. That’s a death sentence for a diabetic.Here’s how to protect your meds:

- Use insulated, waterproof cases. Some have gel packs that stay cool for hours.

- Keep insulin close to your body-inside your jacket, not in your backpack.

- Avoid leaving pills in direct sun. Even in the shade, temperatures inside a backpack can hit 120°F on a sunny day.

- Store all medications in their original bottles with pharmacy labels. Customs and border agents ask for them. So do local clinics.

One Reddit user, u/HimalayanTrekker, lost control of their diabetes at 14,000 feet because their insulin froze. They had to be evacuated. The cost? $4,200. A $15 insulated case would’ve prevented it.

Pre-Trip Doctor Visit Is Non-Negotiable

The CDC says the pre-travel consultation is your best chance to avoid disaster. Yet, only 68% of trekking companies required it in 2023. That number is rising fast-by 2027, 95% will make it mandatory because of insurance rules.Don’t wait until the week before. Go 4 to 6 weeks out. Your doctor needs to:

- Check for heart or lung conditions that make altitude dangerous.

- Prescribe and explain how to use acetazolamide or dexamethasone.

- Write a letter for controlled substances (like strong painkillers or ADHD meds). Some countries require this.

- Confirm your prescriptions are legal in the country you’re visiting.

According to the Himalayan Rescue Association, 83% of serious altitude complications could’ve been avoided with a simple checkup. That’s not a suggestion. That’s a statistic you can’t ignore.

What Not to Do

People make the same mistakes every year. Don’t be one of them.- Don’t rely on local pharmacies. A 2013 survey found 89% of health camps along pilgrimage routes didn’t have acetazolamide, dexamethasone, or nifedipine. You can’t trust them to have what you need.

- Don’t take someone else’s medication. Dexamethasone isn’t a miracle cure. It’s a steroid. Misuse can cause seizures, psychosis, or adrenal crash.

- Don’t sleep during ascent. If you’re climbing and feel tired, rest-but don’t lie down. Sleep slows your breathing. That’s dangerous when oxygen is already low.

- Don’t ignore early symptoms. A headache? Drink water. Rest. Don’t push. If it gets worse, descend. No pilgrimage is worth your life.

Special Cases: Diabetics, Asthmatics, and Pregnant Travelers

Some people need extra planning.Diabetics: Test your blood sugar more often. Cold weather skews readings. Carry glucose tablets. Tell your group where your insulin is stored. Have a backup plan if your pump fails.

Asthmatics: Bring two inhalers. One in your pocket, one in your pack. Cold, dry air triggers attacks. Altitude makes breathing harder even for healthy people. Don’t assume your usual dose will be enough.

Pregnant women: Most experts advise against high-altitude travel after 20 weeks. Acetazolamide isn’t recommended during pregnancy. If you’re going anyway, consult a high-risk OB-GYN. The risks of AMS are higher, and emergency care is limited.

Emergency Tools Beyond Pills

Medications help, but sometimes you need tech.A hyperbaric bag (like a Gamow Bag) simulates lower altitude by pressurizing air around the person. It’s not a cure-but it buys time. Less than 5% of health camps have one, but if you’re leading a group, consider renting one. Some trekking companies now include them in premium packages.

Also carry:

- A satellite messenger (Garmin inReach or Zoleo) to send SOS signals.

- A portable oxygen canister (1-2 liters). Not a replacement for descent-but helpful for short-term relief.

- A small notebook with your meds, allergies, and doctor’s contact info. Paper doesn’t die when batteries do.

Final Checklist Before You Leave

Use this. Print it. Stick it on your fridge.- ☐ See your doctor 4-6 weeks before departure

- ☐ Get prescriptions for acetazolamide, dexamethasone, nifedipine, azithromycin

- ☐ Double your medication supply

- ☐ Store all meds in waterproof, insulated containers

- ☐ Carry original pharmacy labels and doctor’s letter for controlled drugs

- ☐ Pack a first aid kit with ointments, antihistamines, ibuprofen, bandages

- ☐ Bring a backup power bank for glucometers or pumps

- ☐ Tell at least two people in your group where your meds are

- ☐ Know the signs of AMS, HAPE, and HACE

- ☐ Have a plan to descend if symptoms worsen

What Happens If You Get Sick?

If someone in your group starts showing signs of severe altitude sickness-confusion, coughing up pink foam, inability to walk straight-act immediately.Step one: Stop climbing.

Step two: Give dexamethasone (8 mg) or nifedipine (20 mg) if you have them.

Step three: Start descending. Even 1,000 feet helps. Don’t wait for a helicopter. Don’t hope it gets better. Descend now.

And if you’re alone? Use your satellite messenger. Don’t wait until you’re unconscious.

There’s no shame in turning back. The mountain will still be there next year. Your life won’t.

Can I buy altitude sickness medication in Nepal or Tibet?

It’s risky. While some pharmacies in Kathmandu or Lhasa carry acetazolamide, most high-altitude health camps don’t. A 2013 survey found 89% lacked essential drugs like dexamethasone or nifedipine. Don’t rely on local stores. Bring your own supply.

Do I need a prescription for Diamox?

Yes. Acetazolamide is a prescription drug in the U.S., Canada, the EU, and most countries. You can’t legally buy it over the counter. Talk to your doctor at least a month before your trip.

Is it safe to take Diamox if I’m allergic to sulfa?

Acetazolamide is a sulfa drug. If you have a true sulfa allergy (not just a rash from an antibiotic), avoid it. Talk to your doctor about alternatives like dexamethasone for prevention, or focus on slow ascent and hydration.

How much water should I drink at high altitude?

Drink 4 to 5 liters daily. Dehydration worsens altitude sickness. Your body loses more water through breathing in thin air. Don’t wait until you’re thirsty. Sip constantly.

Can I use my regular painkillers for altitude headaches?

Ibuprofen (400 mg) works better than acetaminophen at altitude. It reduces inflammation, which plays a big role in altitude headaches. Take it at the first sign of a headache-not when it’s pounding.

Should I carry oxygen canisters?

Not as a substitute for descent, but as a temporary aid. A 1-liter portable oxygen canister can ease breathing for 10-15 minutes. Useful if you’re stuck waiting for help. But it doesn’t cure altitude sickness. Descending is the only cure.

What if I need to bring insulin or other controlled substances?

Carry them in original bottles with labels. Get a letter from your doctor listing the medication, dosage, and reason. For certain controlled substances (like opioids or stimulants), you may need to file forms with the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration or the International Narcotics Control Board. About 17% of trekking groups need this step.

Dwayne hiers

December 15, 2025 AT 06:57Acetazolamide’s mechanism of action is straightforward: it inhibits carbonic anhydrase in the proximal renal tubules, leading to bicarbonate diuresis and metabolic acidosis, which stimulates ventilation and improves oxygenation at altitude. The 125 mg BID protocol is evidence-based, with a number needed to treat (NNT) of 2.3 for AMS prevention. Side effects like paresthesia are transient and correlate with plasma concentration thresholds above 5 mcg/mL. Don’t confuse this with diuretics-this isn’t about fluid loss, it’s about respiratory drive modulation.

Jonny Moran

December 16, 2025 AT 10:50As someone who’s done Kailash twice and led groups in Nepal, I’ve seen too many people show up with a single ibuprofen and hope for the best. This guide? It’s the real deal. The part about storing insulin inside your jacket? That saved a guy in my group last year when temps hit -15°C. Don’t be that person who blames the mountain. Be the one who prepared. Respect the altitude, and it’ll respect you back.

Daniel Wevik

December 17, 2025 AT 14:20HAPE and HACE are not ‘altitude sickness’-they’re hypoxic organ failures. The window for intervention is narrow. Dexamethasone isn’t a ‘magic pill’-it’s a bridge to descent. If you’re carrying it, you’re responsible for knowing the signs: ataxia, altered mental status, cherry-red lips. And if you’re not carrying a satellite messenger? You’re not trekking-you’re gambling. Your life isn’t a photo op. The 5% of groups that rent Gamow Bags? They’re the ones who come home.

Rich Robertson

December 17, 2025 AT 19:09There’s a cultural blind spot here-people think ‘spiritual journey’ means you don’t need medical prep. But the mountains don’t care if you’re praying or meditating. They only care if your blood oxygen drops below 70%. I’ve seen pilgrims from India and Nepal show up with no meds, no plan, and no clue. This isn’t about Western over-preparation. It’s about basic survival. The fact that 83% of evacuations are preventable? That’s a moral failure, not a medical one.

Thomas Anderson

December 19, 2025 AT 18:35Just bring extra insulin and keep it in your coat. Seriously. That’s it. No need to overcomplicate it. And drink water like it’s going out of style. If you feel weird, sit down. If it gets worse, go down. That’s all you need to know.

Sarthak Jain

December 20, 2025 AT 11:56Bro, i was at gosainkunda last year and my friend got bad headache n dizziness… we gave him ibuprofen n he was fine. But i read somewhere that acetazolamide is better? Is it? Also, can i get diamox in kathmandu? The pharmacy guy said yes but i’m not sure…

Sinéad Griffin

December 20, 2025 AT 16:42AMERICA IS THE ONLY COUNTRY THAT DOES THIS RIGHT 😤💊🇺🇸 Look at how we prepare! Other countries just wing it with chai and prayers. We have science, we have protocols, we have insulated cases with gel packs! If you’re going to the Himalayas and you didn’t get a doctor’s note? You’re not brave-you’re reckless. And if you think a 500mg azithromycin is ‘enough’? Sweetie, no. 🚨

Edward Stevens

December 20, 2025 AT 19:40So let me get this straight-you’re telling me that if I don’t carry a Gamow Bag, a satellite device, two inhalers, dexamethasone, and a doctor’s letter written in triplicate, I’m basically signing a death warrant? And yet, millions of people have done this for centuries without any of it? Huh. Guess I’ll just… not go then. 😌